What encouraged eradication efforts in the 1940s and 1950s that would lead to the widespread use of the Polio vaccine?

An examination by Kendall Carney and Kristin Conwill

The Basics

What is Polio, anyway?

According to the World Heath Organization,

“Polio is a highly infectious disease caused by a virus. It invades the nervous system, and can cause total paralysis in a matter of hours. The virus is transmitted by person-to-person spread mainly through the fecal-oral route or, less frequently, by a common vehicle (e.g. contaminated water or food) and multiplies in the intestine. Initial symptoms are fever, fatigue, headache, vomiting, stiffness in the neck and pain in the limbs. One in 200 infections leads to irreversible paralysis (usually in the legs). Among those paralyzed, 5% to 10% die when their breathing muscles become immobilized.”

Furthermore,

“Polio mainly affects children under 5 years of age,” (who.int).

Background

Check out our timeline!

http://timeglider.com/t/b90db8b9f47006d7?min_zoom=1&max_zoom=100s

Gaining Support

The March of Dimes

- In 1934, Basil O’ Connor, Roosevelt’s adviser, hosts a ball in honor of Roosevelt’s birthday and to raise money for polio research.

- After 4 years of success, Roosevelt creates his own foundation named National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis.

- Later in 1938, Eddie Cantor broadcasts the idea of people mailing dimes to the White House in support of Roosevelt’s new foundation on his radio show.

- Grass root organizations and celebrity sponsors joined the campaign coining the name, March of Dimes.

- March of Dimes became instantly popular and continued to grow. With FDR busy running the country, he delegated the role of President of March of Dimes to Basil O’Connor.

- O’Connor was President for 30 years.

- His first goal was to create local chapters throughout the nation to raise funds and provide aid in order to quickly respond to outbreaks in the region.

- Proved to be a highly effective use of funds and entering 1950 there was 3,100 different chapters run mostly through volunteers.

- Little was known about polio and barely any government money went to public health, research and health care was nonexistent.

- 1951: $1 million had been put towards research to identify all types of polio.

- 1955: $9 million went towards the testing and production of Salk’s vaccine to guarantee the safety and effectiveness of the product before distributing.

- Demonstrates how fearful people were that they would gamble away $9 million in order to ensure its safety before distribution.

- March of Dimes gives research grant to John Enders, Thomas Wellers, and Frederick Robbins who discovered how to grow polio virus in non-nervous tissue.

- O’Connor and Salk became fast friends after meeting in Second International Poliomyelitis Conference in Copenhagen.

- This friendship led to a lot of beneficial polio research and development projects using March of Dimes funding.

- In 1960, March of Dimes builds Salk an institute for biological studies in San Diego

- Being founded by Roosevelt, the foundation had a lot of support immediately. His National Foundation’s balls garnered support from the upper class immediately.

- March of Dimes campaign enacted by Eddie Cantor drew in the middle and lower class by presenting the idea that every dime makes a difference.

- Fundraising appeals made by Elvis, Lucille Ball, Mickey Rooney, Zsa Gabor, Helen Hayes, etc…

The Aspect of Fear

In addition to public campaigns, the element of fear was a powerful influence on new and quick approaches for a Polio vaccine. The US suffered a rising number of cases each summer that lowered morale, especially following WWII. The public reaction and “solutions” to outbreaks also caused concern and distress within communities. Fear of Polio contributed to the rapid efforts of working towards a cure through the amount of outbreaks and reactions to them.

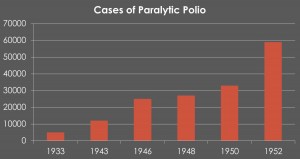

Polio started to become more noticeable with the 1916 outbreak in New York. The cases that summer reached 26,212 and continued to grow in different parts of the country in the following decades. The chart below demonstrates the growing number of cases until the 1952 epidemic effecting thousands (Pomerantz, 3).

Though outbreaks tended to effect one area or another at a time, most of the nation as a whole saw devastating numbers throughout the years. The map below illustrates the number of Polio notifications before the vaccination. These cases are totaled from 1910-1955 (Trevelyan, Smallman-Raynor, and Cliff, 276).

Though outbreaks tended to effect one area or another at a time, most of the nation as a whole saw devastating numbers throughout the years. The map below illustrates the number of Polio notifications before the vaccination. These cases are totaled from 1910-1955 (Trevelyan, Smallman-Raynor, and Cliff, 276). Due to the large spread of the disease, efforts were enforced within cities in an attempt to control Polio. These efforts, however, contributed to the anxiety felt about Polio without much success in defeating the disease or preventing the spread. Among the efforts were quarantining and closing public facilities like schools, pools, and churches. The shutdown of public meeting spaces was also aided by sanitation efforts around cities and towns. Attempts such as these only contributed to and demonstrated the widespread fear of Polio (Wellner, 55).

Due to the large spread of the disease, efforts were enforced within cities in an attempt to control Polio. These efforts, however, contributed to the anxiety felt about Polio without much success in defeating the disease or preventing the spread. Among the efforts were quarantining and closing public facilities like schools, pools, and churches. The shutdown of public meeting spaces was also aided by sanitation efforts around cities and towns. Attempts such as these only contributed to and demonstrated the widespread fear of Polio (Wellner, 55).

The disease had a history of taking the nation’s children’s lives, which, following WWII was a psychological hit to American families. Franklin Roosevelt appealed to a radio broadcast for donations by stating,

“The dread disease that we battle at home, like the enemy we oppose abroad, shows no concern, no pity for the young. It strikes—with its most frequent and devastating force— against children. And that is why much of the future strength of America depends upon the success that we achieve in combating this disease,” (Historyofvaccines.org).

The effect Polio had on children was psychologically devastating to the nation. Mark Sauer, a Polio survivor, notes that,

“polio left kids crippled, and that was an image that this big strong postwar country simply couldn’t abide. We had children lining up in wheelchairs, in iron lungs, whose very vitality [was drained] and everyone’s hope for their future…[shaken] right at the most critical time in their childhoods,” (Wellner, 54).

Polio was a disease that took America’s youth in a time when the country was recovering from a long lasting war. The nation needed to work together to defeat this source of anxiety and depression introduced into its society year after year.

Results!

Efforts due to the March of Dimes Campaign and fear led to the discovery of vaccinations at last. There are four notable dates and developments. The first was in 1935 with the discovery of three vaccines. Unfortunately, they had disastrous results. The second was in 1948 with the test trials by Hillary Koprowski and Tom Norton. Not yet aware that there were three types of polio, this vaccine only developed antibodies for Type II. 1952 was a monumental year with Jonas Salk’s work on the vaccine that could kill all three types of Polio. The vaccine he created was finally approved and licensed in 1954. Finally, in 1959 Sabin created an attenuated vaccine for the Soviet Union. It was taken orally, cheaper, and worked faster, therefore the U.S. adopted it from 1963 – 1999. Vaccines were discovered so the fight was essentially won (marchofdimes.org).

So, what’s the verdict?

The March of Dimes campaign and fear due to reoccurring Polio outbreaks encouraged eradication efforts in the 1940s and 1950s that would lead to the widespread use of the Polio vaccine.

Sources, Sources, Sources

“History of Polio.” Global Polio Eradication Initiative Polio and Prevention. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative, 2010. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://www.polioeradication.org/Polioandprevention/Historyofpolio.aspx>.

“History of Polio.” History of Vaccines RSS. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/timelines/polio>.

“History.” PolioToday. Web. 11 April 2015. http://poliotoday.org/?page_id=13

“NMAH | Polio: Timeline.” NMAH | Polio: Timeline. Smithsonian, 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://amhistory.si.edu/polio/timeline/>.

“Poliomyelitis.” World Health Organization. Web. 11 April 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs114/en/

Pomerantz, Lauren. “Living in Fear: America in the Polio Years.” Teachspace.org. Web. 11 April 2015. http://www.teachspace.org/personal/research/poliostory/fear3.html

Rose, David. “History.” A History of the March of Dimes. March of Dimes, 26 Aug. 2010. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/a-history-of-the-march-of-dimes.aspx>

“Salk Institute – About Salk – History of Salk – Discovery Timeline.” Salk Institute – About Salk – History of Salk – Discovery Timeline. Salk Institute For Biological Studies, 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://www.salk.edu/about/discovery_timeline.html>.

Sass, Edmund. “Polio History Timeline.” Polio History Timeline. University Press of America, 11 Jan. 2005. Web. 18 Apr. 2015. <http://www.eds-resources.com/poliotimeline.htm>.

Trevelyan, Barry, Matthew Smallman-Raynor, Andrew Cliff. “The Spatial Dynamics of Poliomyelitis in the United States: From Epidemic Emergence to Vaccine-Induced Retreat.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95.2 June (2005): 269-293. JSTOR. Web. 11 April 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3694119

Wellner, Karen L. “Polio and Historical Inquiry.” OAH Magazine of History, 19.5 September (2005): 54-58. JSTOR. Web. 11 April 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25161982.